The Colorado River basin supplies water to up to 40 million people and five million acres of farmland across two countries, seven U.S. states, and up to 30 federally recognized Native American Tribes. Since 2000, consumptive uses and losses of the basin’s water have regularly exceeded natural flows, and levels of Lakes Mead and Powell, the largest surface water reservoirs in the U.S., are at historic lows. Consequently, the U.S. government is taking and considering unprecedented steps to reduce water use.

This webpage explains how we got here and what to expect in the months to come. At present, the U.S. Department of the Interior is evaluating a proposal put forth by the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada in May 2023 to voluntarily reduce their water use over the next three years. This proposal seeks to avoid mandatory water cuts unilaterally imposed by Interior, and its temporary water cuts would expire after 2026 along with key operating guidelines and agreements governing Colorado River water allocation. Interior also initiated a legal process for longer-term, post-2026 allocations on June 15, 2023.

Water conservation sought

On June 14, 2022, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Camille Touton stated in a Congressional hearing that “between two and four million acre-feet of additional conservation is needed just to protect critical elevations in 2023.” This volume is 16 percent to 33 percent of the Colorado River’s average annual flow since 2000. The Lower Basin states’ proposal would conserve a volume equivalent to at least eight percent of this average annual flow in light of robust precipitation this past winter.1

Conserving water from 2023-2026

In October of 2022, Reclamation launched several initiatives that could mandate new, uncompensated water cuts and/or pay water users to voluntarily conserve water as soon as summer 2023. These initiatives are intertwined because greater volumes of voluntary water conservation could lessen the need for mandatory water cuts (or vice versa). Voluntary water conservation is largely being funded by the Inflation Reduction Act, which provides $4.6 billion to pay water users to temporarily use less water, lower long-term demand, and restore ecosystems. Meanwhile, mandatory water cuts could be implemented through revised operating guidelines for Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams for the 2023 and 2024 operating years. Although existing guidelines run through 2026, given critically low reservoir elevations in Lakes Mead and Powell, initial water conservation efforts have focused on the years 2023-2026.

The threat of mandatory water cuts

Water levels in Lake Mead have fallen to historic lows as a result of climate change-driven drought and industrial, agricultural, and residential use. Image credit: Anne Lindgren

On October 28, 2022, Reclamation announced that it was beginning a legal process that could mandate new, uncompensated water cuts by revising the operating guidelines for Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams by late summer of 2023. To revise the guidelines, Reclamation released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) that considered alternative approaches (following a National Environmental Policy Act process). Reclamation collected public comments in late 2022 and early 2023 and released a draft SEIS for public review in spring 2023. The original draft SEIS evaluated three different alternatives:

- A no-action alternative consisting of existing agreements and operations

- Mandatory water cuts for Lower Basin users based on legal priority and imposed unilaterally by the Department of the Interior

- Mandatory, equal-percentage water cuts for Lower Basin users that ignore legal priorities and are imposed unilaterally by Interior

A voluntary alternative: the Lower Basin consensus proposal

On May 22, 2023, before the public comment period for the original draft SEIS ended, the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California, and Nevada submitted their own consensus water conservation proposal that would voluntarily achieve at least 3 million acre-feet total in new reductions by the end of 2026. This volume represents about half of the minimum total water conservation requested by Reclamation in 2022 and would rely on federal payments of about $1.2 billion to agricultural water users, cities, and Native American Tribes. All seven basin states requested, and Interior agreed, to withdraw the original draft SEIS and evaluate this new proposal as an alternative in a new draft SEIS with a new public comment period.

Under the Lower Basin proposal, between 2.3 and 2.5 million acre-feet of water conservation would be paid for by the federal government. The remaining conservation would either occur voluntarily without payment or be paid for by state or local entities. At least 1.5 million acre-feet of new conservation would occur by the end of 2024.

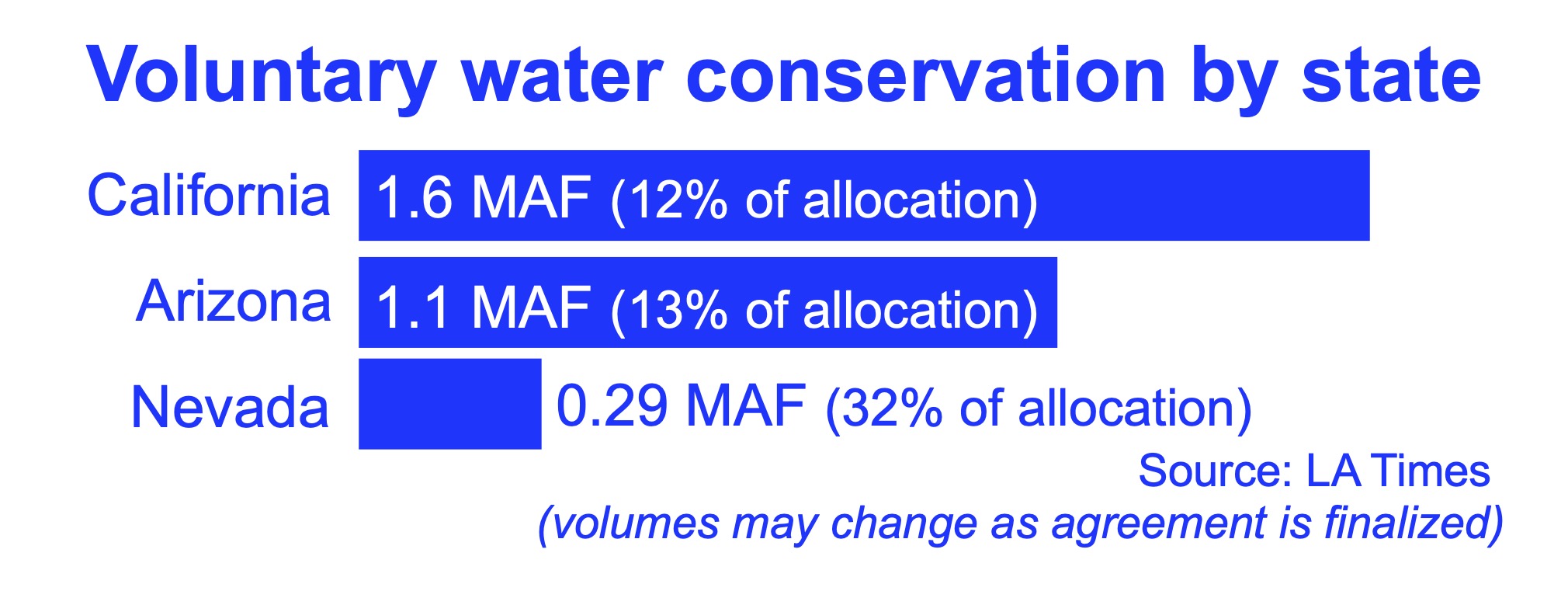

Voluntary water conservation by state in the Lower Basin plan

Under this proposal, payments for 2.3 million acre-feet of the water conservation would occur under the Lower Basin System Conservation and Efficiency Program. This program launched when, from October 12 to November 21, 2022, Reclamation accepted proposals for projects that would pay water users to leave water in Lake Mead. Reclamation offered $330 per acre-foot for one-year agreements, $365 per acre-foot for two-year agreements, and $400 per acre-foot for three-year agreements. Reclamation also accepted water conservation and efficiency project proposals with different pricing. Although some water conservation deals have not yet been finalized, the following deals have been announced or reported:

- Arizona

- Phoenix and Tucson Metro Areas: Eight water providers would receive up to $157.2 million to conserve up to 393,000 acre-feet from 2023-2025, at a price of $400 per acre-foot

- Reclamation reached a water conservation deal with the GM Gabytch Family Limited Partnership in Arizona.

- California

- Coachella Valley Water District: Up to $36 million to conserve up to 90,000 acre-feet (30,000 acre-feet per year) in 2023-2025, at a price of $400 per acre-foot

- Imperial Irrigation District: No agreement has been finalized, but on April 6, 2023, Reclamation announced that it was working towards an agreement to conserve up to 1 million acre-feet (250,000 acre-feet per year) from 2023-2026. More recent reporting stated that the Imperial Irrigation District could receive up to $672 million to conserve up to 800,000 acre-feet through 2026, at a price of up to $840 per acre-foot. Farmers in the Imperial Irrigation District (and Yuma, Arizona) had previously sought conservation payments of $1,500 per acre-foot.

- Palo Verde Irrigation District: $191 million or more to conserve around 477,000 acre-feet from 2023-2026, at a price of $400 per acre-foot

- These agreements implement California’s voluntary offer, first announced in October of 2022, to voluntarily conserve 400,000 acre-feet annually from 2023-2026, or about nine percent of its Colorado River allocation. This voluntary conservation was made contingent upon payments to water users from the federal government and a clear federal commitment to contribute to stabilizing the Salton Sea.

- Native American Tribes

- Gila River Indian Community: Up to $150 million to conserve up to 375,000 acre-feet (125,000 acre-feet per year) in 2023-2025, at a price of $400 per acre-foot

- Reclamation has completed a water conservation deal with the Ft. McDowell Yavapai Nation, and the Quechan Tribe of the Ft. Yuma Indian Reservation submitted a water conservation proposal to Reclamation.

Additional voluntary water conservation programs

Long-Term Lower Basin System Conservation and Efficiency Projects

On May 24, 2023, Reclamation began accepting applications for Lower Basin System Conservation and Efficiency projects generating long-term, durable water conservation benefits. These differ from prior agreements and proposals in that they would provide long-term water savings. Reclamation will accept proposals through July 19, 2023.

Upper Basin System Conservation Pilot Program

In December 2022, the Upper Colorado River Commission announced that up to $125 million would be available to pay water users to conserve water and improve water-use efficiency. This effort restarted a prior System Conservation Pilot Program but greatly ramped up its funding. This program previously spent a total of $8.5 million in the Upper Basin from 2015-2018. The Commission accepted new water conservation proposals from December 14, 2022 to March 1, 2023 and selected 72 of 88 project applications it received. The Commission estimates that the selected projects will conserve as much as 39,178 acre-feet of water at a total cost of about $16 million.2 While the Commission initially offered $150 per acre-foot of conserved water, water users could request higher payments, and the average payment ended up exceeding $400 per acre-foot.

Salton Sea restoration

From 2023-2026, Reclamation will provide $250 million to help stabilize California’s Salton Sea, complementing $583 million in state funding to date. The Salton Sea is an inland lake that is already shrinking and would shrink further due to reduced irrigation runoff caused by water conservation, exposing the community to toxic dust on the lakebed. Avoiding dust exposure is important to the local community and influences the Imperial Irrigation District’s willingness to conserve water and reduce irrigation runoff.

Approximately 80 percent of the Colorado River's water is used to irrigate agricultural fields, like those seen here in Arizona at the border with California.

Image credit: Sundry Photography

Conserving water after 2026

On June 15, 2023, Reclamation initiated another formal legal process under the National Environmental Policy Act to replace the existing operating guidelines for Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams after they expire in 2026. Specifically, Reclamation initiated the public scoping process for a separate Environmental Impact Statement concerning post-2026 operations and is accepting public comments through August 15, 2023 on the scope of operations, strategies, and related issues to be considered. This legal process will probably revisit key issues raised in efforts to cut water use before 2026, but with significantly more emphasis on achieving long-term water-use reductions. Additional key issues that may be considered in formulating the post-2026 guidelines include how to involve Tribal Nations, how and whether to determine relative rights and obligations between the Upper and Lower Basins, federal funding to pay for water conservation, and uncompensated water cuts to be determined by the federal government.

Potential litigation over mandatory water cuts

One key advantage of voluntary water conservation agreements is that they can help to avoid litigation. If Interior adopts the Lower Basin states’ consensus proposal for voluntary water conservation before 2026 or something like it, the probability of litigation over mandatory water cuts will drop significantly. Nevertheless, the Lower Basin states’ consensus proposal does not eliminate the possibility of litigation because, according to the proposal, in the unlikely event that Lake Mead drops to certain levels near minimum power pool, Reclamation could take unilateral action to cut water use. If Reclamation makes unilateral water cuts, it would probably be sued by basin states, Native American Tribes, and/or individual water rights holders. Post-2026 operating guidelines could also raise the possibility of mandatory water cuts if adequate agreements are not reached voluntarily.

A court evaluating such lawsuits would face several key questions:

Did Interior exceed its authority?

If Interior unilaterally cut water deliveries to California, litigation would center on Interior’s authority to do so despite California’s senior legal status. The Central Arizona Project is legally junior to California’s Colorado River allocation and about two-thirds of California’s Colorado River allocation predates the 1922 Colorado River Compact and thus has a senior status.3 Although Reclamation would be on stronger legal ground cutting deliveries to the Central Arizona Project given its junior legal status, this could mean that some Tribes and cities like Phoenix and Tucson could face heavy supply reductions while farmers in California and elsewhere receive continued deliveries.

Would lawsuits go directly to the U.S. Supreme Court or to federal district court?

If a lawsuit over Colorado River cuts involves two or more states, it would go directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.4 Lawsuits between individual water rights holders and Reclamation could start in federal district court.5

The Central Arizona Project Aqueduct, which transfers Colorado River water each year to cities, Tribes, and farms, is seen near Parker, Arizona.

Image credit: David McNew / Getty Images

Anticipated key dates in the coming months

- June 15 - August 15, 2023: Reclamation will accept public comments regarding the scope of issues to be considered in the EIS concerning post-2026 operations.

- July 2023: Reclamation will finish accepting applications for long-term system conservation and efficiency projects in the Lower Basin.

- Summer 2023: Reclamation will continue negotiating and finalizing short-term water conservation deals in the Lower Basin. Revised draft pre-2026 SEIS that evaluates the Lower Basin consensus proposal released for public review, including 45-day comment period.

- August 2023: Reclamation announces shortage designation for calendar year 2024.

- Late 2023: Final pre-2026 SEIS released, announcing whether Interior adopts the Lower Basin consensus proposal or something like it.

Page last revised: June 15, 2023

Thanks to Buzz Thompson, Felicia Marcus, Martin Doyle, and Zachary Sugg for their comments and review.

Notes

1All seven Colorado River basin states supported the submission of the Lower Basin Plan to Reclamation and requested that Reclamation evaluate it, but the Upper Basin states did not endorse the Lower Basin plan. This plan focuses on Lower Basin water conservation because most Colorado River water consumption happens in the Lower Basin and Interior has legal authority to mandate water cuts in the Lower Basin that it lacks in the Upper Basin, among other reasons. Upper Basin states have undertaken separate water conservation initiatives, as detailed later in the webpage.

2 The Upper Basin System Conservation Pilot Program generally does not protect water savings all the way downstream to Lake Powell or other reservoirs, raising the possibility that other water users may take the conserved water.

3 According to the Compact, water rights that predate it, known as “present perfected rights,” “are unimpaired by this compact.” Colorado River Compact art. VIII, 1922. California has over three million acre-feet of these senior rights, with 2.6 million acre-feet owned by the Imperial Irrigation District. Arizona v. California, 547 U.S. 150, 174 (2006). Over one million acre-feet of these senior rights that predate the Compact are in Arizona, with about 780,000 acre-feet of those owned by Native American Tribes. Arizona v. California, 547 U.S. 150, 169 (2006).

4 Also, any lawsuit would go directly to the U.S. Supreme Court if it invokes the Court’s retained and exclusive jurisdiction over adjudication of water from the mainstream of the Colorado River in Arizona v. California. The scope of the Court’s Arizona v. California jurisdiction could be elaborated in a different case currently before the Court, Arizona v. Navajo Nation, No. 21-1484. Oral argument was March 20, 2023.

5 This occurred in 2003 when California’s Imperial Irrigation District challenged Reclamation’s authority to reduce its water deliveries. Imperial Irrigation Dist. v. United States, No. 03-CV-0069W (JFS) (S.D. Cal. Jan. 10, 2003).

![[Woods Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-woods.png)

![[Bill Lane Center Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-billlane.png)