June 07, 2018 | Water in the West | Insights

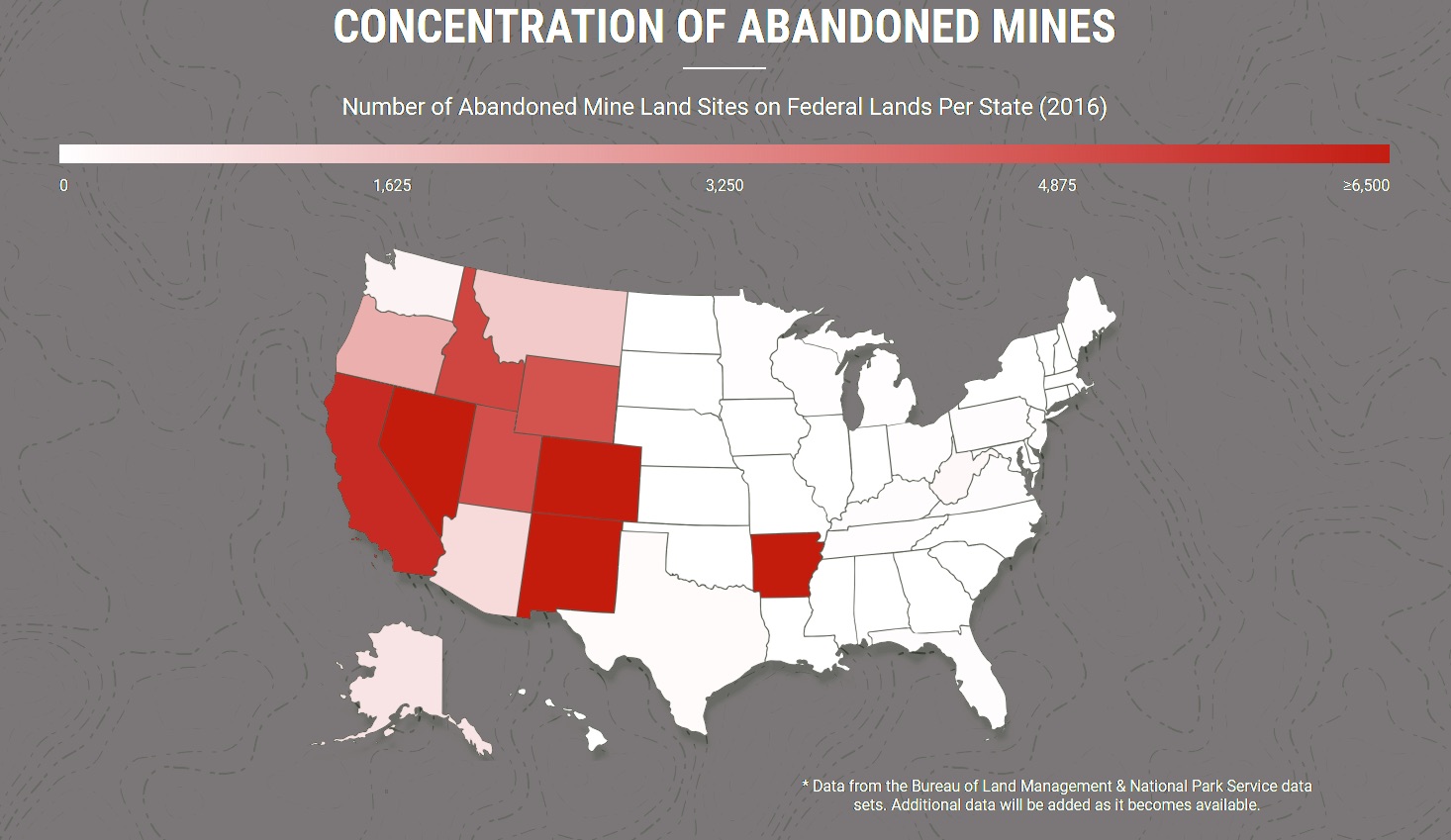

The General Mining Act of 1872 (sometimes referred to as the ‘Hardrock’ Act) provided for the free and open development of vast expanses of the western U.S. to any citizen hoping to cash in on the promise of gold, silver, copper, and other minerals. Because much of the foundation of U.S. mining law was predicated on the ‘right to mine,’ 32 of 50 states have been left to contend with roughly half a million abandoned mines. The legacy of this history is particularly striking in the western U.S. where estimates by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) suggest that 40% of headwaters streams are contaminated from historical mining activity. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: The concentration of abandoned hardrock, uranium, and coal mines according to the Bureau of Land Management. Abandonedmines.gov.

Without some form of remediation, a laundry list of potential damages to human and aquatic health are associated with abandoned mines. While many of these sites are small or isolated, some of them are not. And the sheer number of extant abandoned mines can lead to a compounding of contamination sources. On top of all of this, many states in the western U.S. are experiencing unprecedented growth, leading to increased recreation on public lands and increased potential for exposure to dangerous contaminants from abandoned mines as a result.

The current menu of options for dealing with abandoned mines is limited by a number of factors, namely funding constraints and liability. If the impact of the abandoned mine is significant enough, the site may be eligible for listing on the National Priority List (NPL) of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) program, more commonly known as the Superfund Program. While this program is an important tool for cleaning up the worst sites, designation on the NPL doesn’t necessarily mean that a site will be addressed. Moreover, many of the abandoned mines dotted throughout the western U.S. will likely never be candidates for the NPL.

With the operators responsible for the degradation long gone, impacted organizations and communities are tasked with the herculean job of figuring out how to fund and conduct remediation if listing on the NPL is not pursued.

“Throughout the country, state and tribal [Abandoned Mine Lands] programs are working hard to return lands and waters impacted by legacy hardrock mining to productive use. But available resources are very limited in comparison to the scale of the problem. Every source of help is needed to contend with that problem...” explains Ms. Autumn Coleman, of the Montana Department of Environmental Quality.

One potentially promising, though controversial, path forward to address these resource limitations is Good Samaritan legislation. Good Samaritan legislation reduces liability for willing volunteers engaged in remediation activity and relaxes the stringency of the environmental standards to which cleanup activities are expected to adhere. As states and communities seek to deal with the West’s “sleeping giant” as Dr. Karletta Chief explains the problem, understanding the role of Good Samaritan legislation will be critical.

The nuts and bolts of remediation

Remediation efforts primarily deal with two types contaminants: inorganic or organic substances. Comprehensive thresholds for both inorganic and organic contaminants are set by the EPA and are predicated on protecting human health, although other standards for aquatic life, livestock and wildlife health also exist. In the context of abandoned mines, nearly all contamination issues spring from exceedance of the inorganic thresholds, which can include an excess of lead, zinc, copper and other heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, antimony, selenium, and uranium.

The source of inorganic contaminants can vary depending on the site. Because many extraction processes used to remove ore from a deposit were designed to extract higher quality ore as efficiently and economically as possible, the primary source of contamination is frequently waste rock. A term that broadly refers to the rock and ore—often times of a lower grade than that of the extracted material—left behind following extraction. Other sources of contamination include mine water (water that collects in a mine due to precipitation); surface and groundwater flow; overburden (sometimes referred to as waste rock); spent ore; and mill tailings.

The combination of multiple sources for multiple contaminants carries with it various and sundry environmental complications. Chief among these is the generation of highly acidic water rich in metals (known as Acid Mine Drainage), which happens when metal sulfide minerals are oxidized and enough water is present to mobilize the sulfur ion. Acid mine drainage changes the pH of adjacent waters, which can affect human health, aquatic life, and vegetation for up to 100 years.

This laundry list of potentially damaging side-effects continues. Sedimentation and the subsequent mobilization of adjacent chemical pollutants is another common problem owing to the size of disturbed earthen material in the mining process. Cyanide can also be a concern because of its historical use in mining operations as part of ore processing. Additional issues related to air emissions and downwind deposition of both particulate material and certain gaseous emissions related to mining, as well unique structural concerns related to waste units and mine site integrity, exist.

The rub of it all is that the identification of the source—or sources—of contamination is only the first step for a community endeavoring to clean up a site. Once a contamination problem is identified and the acceptable thresholds are exceeded, the question then becomes how to mitigate or eliminate the source, manage any exposure pathways, and control receptor exposure.

“In the case of inorganic contaminants, the three general options that exist are removal, in-situ stabilization, and attenuation,” explains Stanford University Professor Scott Fendorf. Of these options, removal is the most aggressive of the potential remediation pathways, while in-situ stabilization and attenuation may be more appropriate for smaller scale efforts (e.g. less contamination or less potential to negatively impact downstream communities).

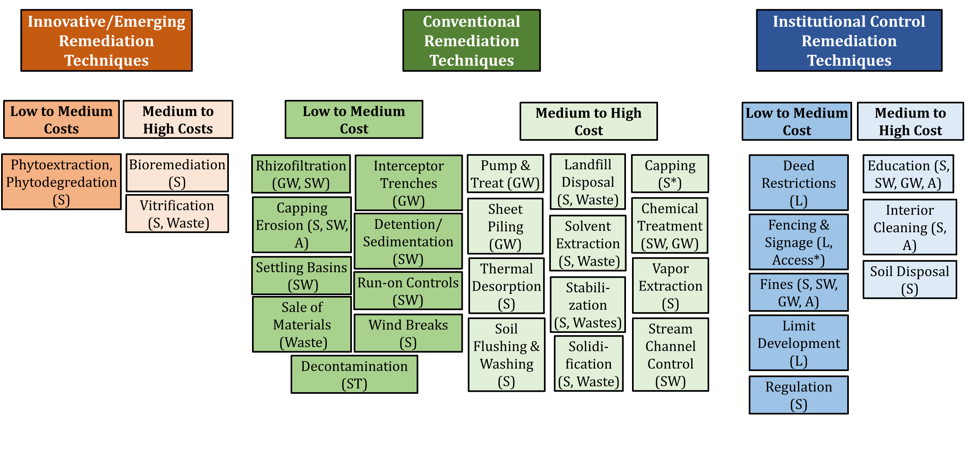

Remediation options can be further divided in to a number of different categories, including emerging, conventional and institutional. A number of which have been identified by the EPA as viable pathways to remediate these sites under a variety of circumstances (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Existing remediation pathways for dealing with abandoned hardrock mines according to the U.S. EPA. Institutional, emerging, and conventional techniques are broken out according to their anticipated costs. Each individual technique also outlines the medium acted upon (e.g. if the method targets soil, S is indicated in parenthesis). The abbreviation for mediums is as follows: S is Soil, SW is surface water, L is land, GW is groundwater, A is Air, and ST is structure.

Several of the low-cost options listed by the EPA (Figure 2) are relatively easy to implement and potentially reduce the amount of contamination in water and soil. For instance, Trout Unlimited has had success in Pennsylvania where it is helping to “bring the land and water back to pre-mining conditions.” A variety of other techniques can be used to stabilize soils and reduce the release of contaminants into waterways as well. Despite the number of viable choices for removing contaminants from degraded waters and soils, the regulatory options for groups to pursue these actions outside of CERCLA are limited.

CERCLA (e.g. Superfund Designation) based remediation

Although Superfund has its own set of issues, it remains the gold standard for remediating abandoned mine sites. CERCLA, the overarching law governing both the NPL and Superfund program, was enacted on December 11, 1980 after a series of highly public, toxic waste sites such as Love Canal and Valley of the Drums in the late 1970s. The law grants EPA authority to clean up designated sites through either short-term removals or long-term remedial response actions.

There are a number of potential pathways for site cleanup under CERCLA. In the event that a responsible party can be found, the EPA can work with them directly to cleanup a site and avoid official Superfund designation. These Superfund Alternative sites still undergo the same process as sites designated as Superfund, but “can potentially save the time and resources associated with listing a site on the NPL.” There are also various. state level approaches, which address remediation of abandoned mines. Regardless of responsible party, sites can also be listed on the NPL, which the EPA has the authority to put the most hazardous sites on.

If a responsible party cannot be identified—as is the case for most abandoned mine sites—listing on the NPL is currently the best option to obtain necessary funds and support. When the law was first passed, cleanups of NPL sites were funded by a tax on chemical and petroleum industries (Superfund), sometimes referred to as the polluter pays tax. From 1981-1995 the Superfund tax generated $12.7 billion to be used for remediation efforts. Contrary to what the name might suggest, the tax funding for CERCLA hasn’t been reauthorized since 1995.

What that means is that the Superfund, which historically provided money to sites for cleanup, has been functionally empty since 2003. Since the “fund” component of the Superfund program has been essentially taken out, it now relies on congressional appropriations which have declined over the years, slowing the pace of cleanups. According to Congressman Frank Pallone from New Jersey, “funding for these cleanups has dropped dramatically since the Superfund tax expired in 1995, meaning fewer cleanups are started and even fewer are finished.”

The issues Congressmen Pallone points out are only compounded when considering that even after the initial remediation efforts have been undertaken, the costs associated with operation and maintenance of these site can be prohibitive. For example, the estimated capital cost for the Smuggler Mountain Superfund site in Aspen, Colorado (which was removed from the NPL in 1999) was almost $1.9 million dollars, with estimated annual O&M costs of $31,000. In a more extreme case, the Iron Mountain Mine in Redding, CA, which has been listed as a Superfund site since 1983 spends $5 million per year with no end in sight. Looking at the bigger picture, the EPA estimated that no more than 20% of the cleanup efforts needed could be completed by 2034 (using the 2004 funding allocations as a baseline).

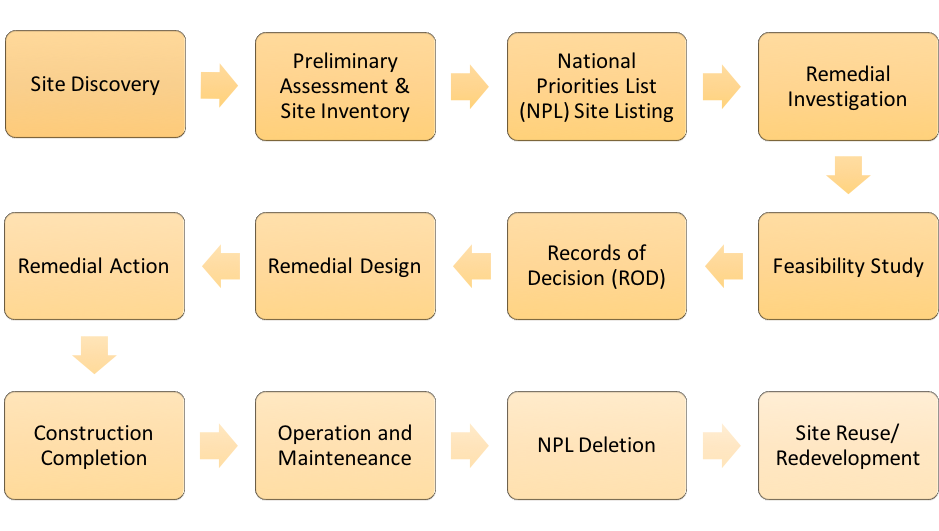

And if the price tag wasn’t enough, sites listed on the NPL are also subject to a lengthy approval, regulatory, and cleanup process. To date, there are 1346 sites listed on the NPL and only 399 sites have been “deleted” from the list. In almost all cases, the road from site discovery to deletion from the NPL is a long one (Figure 3). From the time a site is discovered to the time it is officially listed on the NPL can take between 4-10 years alone. Following this, the site will undergo a number of steps including remedial investigation, a feasibility study, and a public comment period. And then remedial design and cleanup action can finally begin. What all of this means is that even if a site is listed on the NPL, it can take decades for the remedial efforts to even begin.

Figure 3: Process for site listing on the NPL according to the U.S. EPA.

Social factors can also complicate the Superfund process. Many communities are concerned with the stigma of being associated with a Superfund site. According to a former EPA employee, “If there are conflicting opinions or pushback in a community around a potential Superfund designation, it can be very difficult to move the process forward. Support from local and state/tribal government is especially important—without that concurrence, listing a site to the NPL is unlikely.” For example, in Silverton, Colorado many residents fought Superfund designation until pollutants poured out of the Gold King mine into the Animas River, turning it yellow. One resident in Silverton, Colorado had feared designation would “stigmatize the town and turn away tourists.” Residents also feared that property values would go down, investment opportunities would disappear, and their input would be disregarded once the federal government was involved.

However, this is not always true—different sites have experienced negative, neutral, and in some cases, positive impacts to their property values. All of which leads to critical and central questions about environmental justice especially when downstream and disadvantaged communities are the most impacted. Karletta Chief and others at the University of Arizona are currently engaged in work to address these issues on the Navajo Nation following the Gold King Mine spill, which bring the need to do something about these sites in to sharp focus.

The potential role of Good Samaritans in addressing abandoned mines

One potential avenue to help to quickly address the environmental and health related impacts of abandoned mines is through enhancing the legislative protection for volunteers. Currently, these individuals and groups face a number of challenges, namely liability and lack of funding. And this is where the current notion of extending Good Samaritan protections for groups seeking to improve water quality, restore fish populations, or otherwise improve environmental condition related to abandoned mine contamination fits in.

Good Samaritan laws are commonly thought of in a medical context, where they deal with the protection of volunteers and other personnel who provide assistance during an emergency situation. Using this principle as a foundation, efforts to enhance federal protection for volunteers by limiting liability for good faith actions taken to remediate mines and waste sites dates back to 1999 in the U.S.

Concerns about liability stem from the four categories of potentially responsible parties that can be held liable for the immense costs associated with remediating a site under CERCLA, two of which could potentially apply to Good Samaritans. There is also concern that an environmental Good Samaritan could be held accountable for point source discharges under the Clean Water Act. After all, it was during an effort by the EPA to clean up the Gold King mine that a devastating spill occurred leaving EPA responsible.

Given the scale of potential risk, the bills seeking to address Good Samaritan remediation efforts focus on reducing liability by relaxing the stringent environmental standards to which current cleanup activities are held under traditional CERCLA rules or the Clean Water Act. Although the EPA put forward a policy memorandum on protecting volunteers from CERCLA liability in 2007, the issue of liability under the Clean Water Act remains a challenge that could be addressed by Good Samaritan legislation.

And it is this loosening of existing regulation, even if it is to reduce liability for volunteers, that “causes concern among many long-time supporters of those standards,” explains Leon Szeptycki, executive director of the Water in the West Program. Another source of opposition to the Good Samaritan legislation is that it may allow mining companies to take advantage of the liability waiver to the Clean Water Act according to Red Lodge Clearinghouse. The concern being that some Good Samaritans may act in their own self-interest instead of focusing on truly cleaning up the site if the law providing for regulatory relief also allowed re-mining of any ore found at the site and ownership of any valuables they find in the mine tailings. Leaving the door open to the potential for contaminated mine sites to be left in “in worse shape” than they were found.

Groups advocating for Good Samaritan legislation point to the need for practical, albeit potentially imperfect, solutions to contend with the sheer magnitude of the abandoned mine issues facing the U.S. Considering that many of the sites are already polluting waterways and soil and in violation of the Clean Water Act, these groups suggest that there is at least some urgency to push the dialogue from a little less talk to a little more action. Although Good Samaritan projects will never take place at a scale to address the full scope of the abandoned mine problem, they do provide benefits to specific watersheds and provide an important opportunity to improve new remediation methods.

“Advocates of Good Samaritan cleanups believe that it is important to make progress in improving water quality and reducing contamination, even if it falls short of what we might require of a more traditional party to a CERCLA cleanup,” says Szeptycki.

Initial pilot sites indicate that these Good Samaritan groups can implement highly effective, lower-level interventions to successfully combat legacy contamination issues throughout the U.S. For instance, the ‘Environmental Good Samaritan Act’ passed by the state of Pennsylvania provides enhanced protections to third party groups engaged in abandoned mine reclamation. Since the passage of that Act in 1999, groups comprised of local government, community members, corporations, and conservation groups among others have taken on the reclamation of 79 reclamation projects in 20 counties. And other states have expressed support for and interest in Good Samaritan legislation including Montana. “Unfortunately, the existing state and federal grants do not provide consistent or adequate funding. To address the hardrock abandoned mine land problem there is no question that the greatest need is funding. That’s where Good Samaritan volunteers come in to try and help fill that gap,” said Coleman.

Although individual states are making progress towards reducing liability for willing volunteers, at the federal level the regulatory barriers these groups face in implementing viable techniques at a larger scale persist. And thus far, the inability to find some sense of shared mission that allows groups to test whether smaller scale efforts can start to affect meaningful change leads to the frustrating conclusion that we may be making perfect the enemy of good when it comes to abandoned mine cleanup.

Where do we go from here?

Superfund is a well-established, highly effective program to address the pollution associated with abandoned mines in the U.S. But it lacks consistent and reliable funding and is subject to political whims which are quick to change. As a result, CERCLA has left untouched the large majority of contaminated sites in the U.S., many of which are currently polluting soil and water even as this piece is written. Meanwhile, we have a number of proven, implementable techniques in our remediation arsenal, some of which can be done with a high degree of confidence and relatively lower costs to the benefit of many communities—particularly rural and disadvantaged ones.

There are legitimate questions about Good Samaritan legislation. But before writing the option off as untenable over concerns that third parties may take advantage of the liability waivers for profit or that there is simply no way to relax laws to reduce liability for willing volunteers, we need to take a hard look at the reality of the problem. Is there really no way to tailor a piece of legislation narrowly enough to enact some real good? Moreover, where state-level Good Samaritan legislation has been passed, it doesn’t appear to have significantly eroded environmental protections in the region or opened the door for third parties to turn a profit on remediation. To the contrary, evidence in states like Pennsylvania suggests that the statewide protections have instead galvanized unlikely groups of partners to take on meaningful actions in a third of the state’s counties.

If we were to sum up the state of the issue in one sentence, it might go something like this: there are currently a mind-boggling number of contaminated mine sites in the U.S. that may not be eligible—or face significant opposition to—listing on the NPL, which doesn’t actually have the funding to support the majority of them anyway. And to put all our eggs in that basket essentially disregards the number of proven, cost-effective remediation techniques available to volunteers who really want to help.

Interested parties need to be actively involved in dialogue about how best to protect both impacted communities and the environment in the context of abandoned mines. And we should work to maintain the integrity and long-term viability of our country’s foundational environmental laws, including the Clean Water Act and CERCLA. But at this point, we cannot afford to get bogged down in hypothetical debate without making real, on-the-ground progress towards cleaning these sites up. As Szeptycki suggests, “If we created a program that really worked for Good Samaritans, that may allow some positive experimentation as well as on the ground improvement in water quality. If we could do that, it would help to establish a better foundation for any related programs going forward.”

The scale and urgency of this problem requires actionable solutions. While some of the pathways to remediation may not be perfect, limiting the ability for some people to do anything in the hopes that an underfunded program can someday do everything amounts to sitting on the bank of a river hoping a fish might jump in to your lap. It may happen, but chances are we’re better off if we grab a rod and start trying ourselves.

The Berkeley Pit is a former open pit copper mine in Butte, Montana. This site is currently listed on the NPL under CERCLA. Source: Wikicommons, CC 3.0 Jurgen Regel.

![[Woods Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-woods.png)

![[Bill Lane Center Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-billlane.png)