November 27, 2017 | Water in the West | News

New research finds hydraulic fracturing wells and domestic wells are found closer together than expected.

Photo credit: Scott Jasechko

Although the majority of Americans get their drinking water from a municipal, public supply, 1 in 7 rely on private water wells. Though wells for drinking water and wells for oil and gas production are known to exist in the same geographic regions, their proximity to one another across the United States was uncertain.

Previous reports from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on the potential safety and contamination issues involved with hydraulic fracturing impacts to drinking water have focused mainly on public water systems without delving into the status of private wells.

“Forty-five million Americans rely on private groundwater wells for their drinking water,” says Scott Jasechko, assistant professor at Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, University of California at Santa Barbara. “We wanted to address the knowledge gap on how close private wells are to hydraulically fractured wells.”

In a study published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Jasechko and co-author Debra Perrone, formerly a post doctoral scholar with Stanford’s Water in the West program and now an assistant professor in the Environmental Studies Program at University of California at Santa Barbara, determined what percentage of domestic groundwater wells might be next-door neighbors to active hydraulic fracturing.

Unlike public water supplies that undergo routine testing, water testing of private wells is voluntary and contamination events might go unnoticed by the well owner.

The study found that more than half of hydraulically fractured wells lie within 2 to 3 kilometers of a domestic well—potentially close enough for contaminants to enter these wells, should they be released by hydraulic fracturing operations.

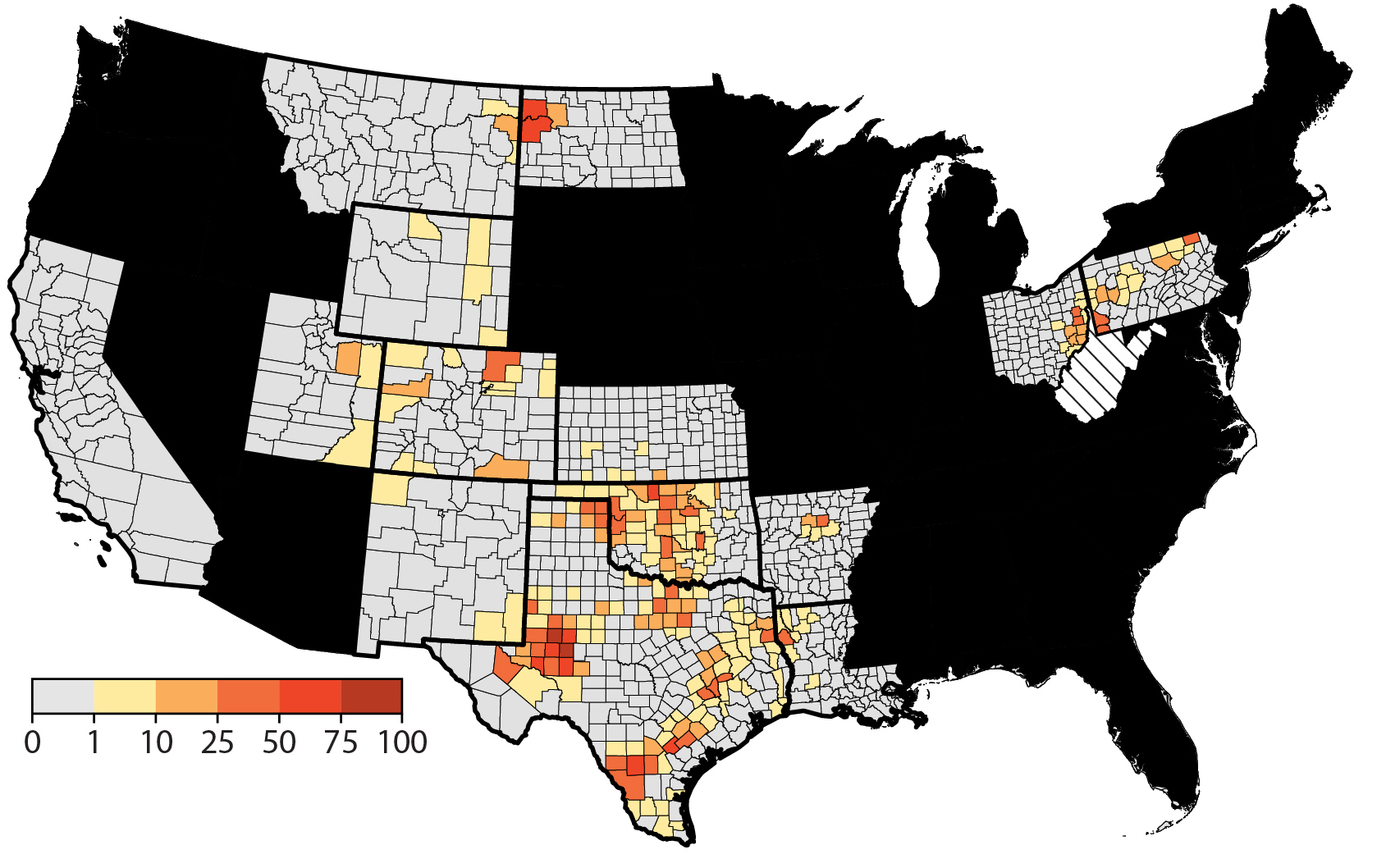

Map of the United States showing the percentage of domestic groundwater wells constructed between 2000 and 2014 that lie within a 2 km radius of at least one hydraulically fractured (stimulated during 2014).

How Close is Too Close?

The researchers concentrated on 14 states spanning the United States that had an active hydraulic fracturing program in 2014, and collected locations for all oil and gas wells that were stimulated for production in 2014. The team then plotted domestic water wells that were constructed between 2000 and 2014, to see how close the domestic groundwater wells were to wells for hydraulic fracturing, and oil and gas production. They chose these recent years to improve the chance that the groundwater wells were being used.

“In some states, it is difficult to identify abandoned wells due to lack of information or inconsistency in state water datasets,” said Perrone. “To increase the likelihood of a domestic-water well being used in 2014, we focused on wells constructed between 2000 and 2014.”

The goal was to identify any domestic water wells that sat within 2 kilometers of a hydraulically fractured well. Previously published studies suggest that chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing may be able to migrate horizontal distances 1 to 3 kilometers, so wells within 1, 2 and 3 kilometers were identified.

Potential Pollution Problems

Contamination from oil and gas extraction can occur in a few ways, including a spill at the ground surface, a “frac hit” where injected fluids enter a nearby pre-existing well during injections, or with a failure of well integrity. Spills are the most common, with an average of about 1 in 40 hydraulically fractured well sites experiencing that type of contamination event.

"We wanted to better understand the risk to domestic water wells," said Perrone. “If a contamination event were to occur, how many wells have the potential to be impacted?”

After collecting all the well location data, the team found that more than 50 percent of hydraulically fractured wells stimulated in 2014 were within 2 kilometers of domestic water wells. Noting that spills have been documented at both hydraulically fractured and conventionally mined oil and gas wells, the team expanded their analysis to include traditional oil and gas wells. They found similar numbers: more than 50 percent of oil and gas wells were within 2 kilometers of at least one domestic well.

Combating Contamination

Perrone pointed out that the proximity alone of hydraulic fracturing wells and domestic groundwater wells doesn’t mean there will be contamination.

“Our findings emphasize that determining how frequently hydraulic fracturing impacts our groundwater quality is important to maintaining potable, safe drinking water across the United States,” said Perrone.

Identifying “hot spots” of potential contamination from oil and gas mining can help focus research and policy efforts in protecting groundwater.

“Given that we have limited resources at the EPA, federal grant agencies and universities, I'm hoping this study helps us to hone in on areas that are most important in terms of proximity to hydraulic fracturing,” said Jasechko.

Perrone hopes their work will help policy makers not only focus on areas of concern, but spur conversations between the water and energy sectors.

“It's important to consider oil and gas production more broadly and its potential impacts to groundwater resources,” she said. “Groundwater is a critical resource for many communities. Determining how oil and gas activities can impact groundwater is important given the close proximity of many domestic water wells to oil and gas activities.”

Debra Perrone was formerly a postdoctoral scholar at the Water in the West program and the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering at Stanford University and is now an assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of California at Santa Barbara. Scott Jasechko was formerly an assistant professor of geography at the University of Calgary and is now an assistant professor in the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

For more information, read the research brief.

Contact

Debra Perrone, Stanford University and UC Santa Barbara, 805.893.2968, perrone@ucsb.edu

Scott Jasechko, UC Santa Barbara, 415.510.1743, jasechko@bren.ucsb.edu

Devon Ryan, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, 650.497.0444, devonr@stanford.edu

![[Woods Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-woods.png)

![[Bill Lane Center Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-billlane.png)