January 27, 2017 | Water in the West | Insights

To anyone following coverage of the storms pummeling California with rain and snow, the fact that a quick google search including the words “drought” and “over” pulls up pages of headlines does not come as a big surprise. The flurry of stories weighing in on whether the state’s punishing drought is actually over range from sobering (a rather apocalyptic combination of extreme avalanches and flood warnings) to hopeful (350 billion gallons added to critically depleted reservoirs). Given the weather—and maybe more importantly, all the stories about the weather—it’s difficult not to wonder if the most recent bout of wintry precipitation spells out the end of California’s drought.

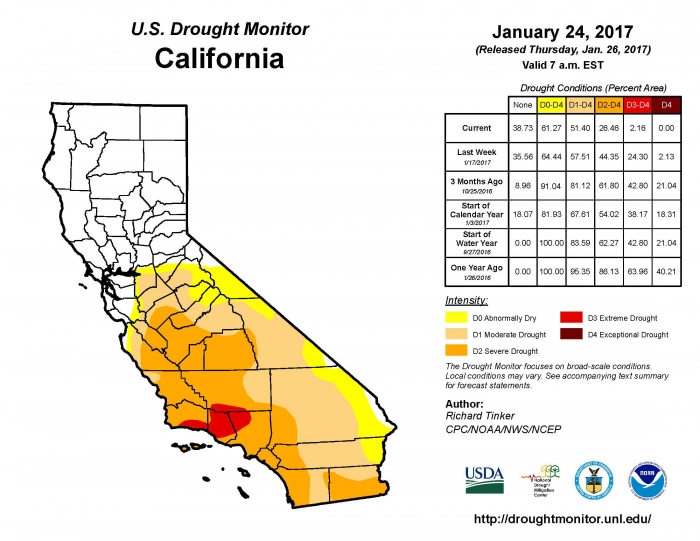

While there are several ways to approach the question of whether or not this drought is over, in one respect the answer is relatively straightforward. As of January 24, 51 percent of California was still in some form of drought, down from 95 percent a year ago. Only 26 percent of the state is in severe drought or worse, down from 86 percent a year ago. These numbers are only part of the story, however, and gloss over the question as to what lessons the current deluge may hold for California’s water future. Whatever the verdict on these particular storms in this particular drought, California will still face changing hydrologic conditions due to climate change and need prudent conservation strategies that are capable of more successfully preparing the state for its next drought.

Substantial increases in the Sierra’s snowpack have been one of the primary narratives in many media stories related to the 2017 storms. Attention that makes sense given that roughly 90 percent of California’s annual precipitation falls in the form of rain and snow between October and May. Historically, the Sierra snowpack has acted as a supplemental water supply reservoir with snowmelt runoff providing inflows to depleted reservoirs like Lake Shasta and Lake Oroville as well as to streams and rivers. And without a doubt, the storms of 2017 have been remarkable in this respect. At the beginning of 2017, SNOTEL snow sensor reports placed snow water equivalence (SWE)—the depth of water contained within the snowpack if it were melted—largely between 0 and 50 percent of historical averages. After January’s round of storms, average snowpack in the Sierra rocketed to 164 percent of normal, with some individual stations recording increases in SWE that exceeded 220 percent from January 1 to January 18, 2017.

The amount of precipitation as rain and snowfall is only one part of a more complex story. In California, the timing of precipitation has also worked to ensure a consistent source of water for both people and agriculture throughout the drier, warmer summer months when regional precipitation drops off significantly. However, the timing of spring runoff has been shifting in large part due to warmer temperatures associated with climate change. For instance, during the state’s 2015-2016 water year, initial snowpack conditions tracked precipitation conditions. As of April 1, 2016, the northern Sierras had received an average amount of precipitation and an average snowpack. By May 1 of 2016, the snowpack had melted to 43 percent of normal for that date because of above average temperatures. This story is further corroborated by observed shifts in western hydrology related to climate change; including hydrograph shifts to earlier peak runoff and transitions from snow to rain dominated precipitation patterns. Simply put, there is good indication that the state is already suffering one of the predicted effects of climate change – a smaller and faster melting snowpack—and it remains to be seen how long all the most recent snowfall will last.

Moreover, there are still big and unanswered questions about how well the state’s policies and infrastructure can navigate these changing hydrologic conditions in the periods of drought to come. In addition to what we already know about the cycles of drought in a Mediterranean climate, recent research conducted by Deepti Singh, Noah Diffenbaugh and others at Stanford University suggests we might face more extreme and frequent droughts moving forward. Singh and Diffenbaugh’s work indicates that the frequency of atmospheric conditions capable of giving rise to extremely hot and dry conditions like those experienced recently is increasing, which does not necessitate the end of extremely wet years. In light of this information, the state would do well to examine what the consequences of warmer winters and a faster melting snowpack mean for its water infrastructure and management regime, both of which were developed with a more persistent snowpack in mind.

Recently, state water officials did move to keep current water conservation measures in place, at least through May and the end of winter precipitation. The conservation measures that remain in place after the State Water Control Board’s relaxation of rules in 2016, however, are overwhelmingly voluntary. Last May, 80 percent of water agencies (including many in the San Francisco Bay Area) put forth a new water savings target of zero when the Sierra’s snowpack returned to average conditions. Unfortunately, there is no guarantee that this run of increased precipitation will last. Without more permanent and long-sighted conservation objectives, California is left similarly exposed when the next drought rolls around.

Emerging from this constellation of research and observation is the argument that the most important long-term consideration is not so much if a month of wet weather—or even a season of it—heralds the end of a drought. Although higher reservoirs, more soil moisture and flowing streams can certainly help to alleviate significant and painful pressures on agriculture, municipalities and people in the short-term. Rather, it seems to suggest that this is an excellent time to push our questioning beyond the immediate and symptomatic diagnosis of “drought” or of “no drought.” More lasting conservation measures, better reservoir and watershed management, updated flood control, enhanced stormflow capture and expanded water storage might generate less buzz, but are the backbone of more resilient and practical western water infrastructure moving forward.

![[Woods Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-woods.png)

![[Bill Lane Center Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-billlane.png)