April 19, 2018 | Water in the West | News

Recent analysis of groundwater sustainability agencies shows need to include nongovernmental stakeholders in decision-making process.

For local communities, complying with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), the law passed in 2014 that was California’s first statewide framework for managing groundwater, has been no easy task. A recent study in the journal California Agriculture examined some of the challenges rising to the surface in large, agriculturally-oriented basins as local governments form groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs), particularly for agricultural water users who have been pumping groundwater with private rights for decades. These GSAs are required to develop groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) by 2020 in critically overdrafted basins, or by 2022 in other high and medium priority basins. The analysis highlights that creating effective governance at the basin scale, while still accounting for the interests of agricultural water users, is best pursued through multi-level governance structures that include nongovernmental entities, such as nonprofits, farmers, and ranchers.

“Meeting SGMA’s sustainability goals will require making decisions across an entire groundwater basin, but stakeholder engagement and participation can be more challenging at large scales. We’re finding that governance structures in which decision-making is shared across multiple levels within a given basin includes more voices and perspectives in the GSA process, and addresses concerns about retaining local autonomy,” said Esther Conrad, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford’s Water in the West program and the Gould Center for Conflict Resolution.

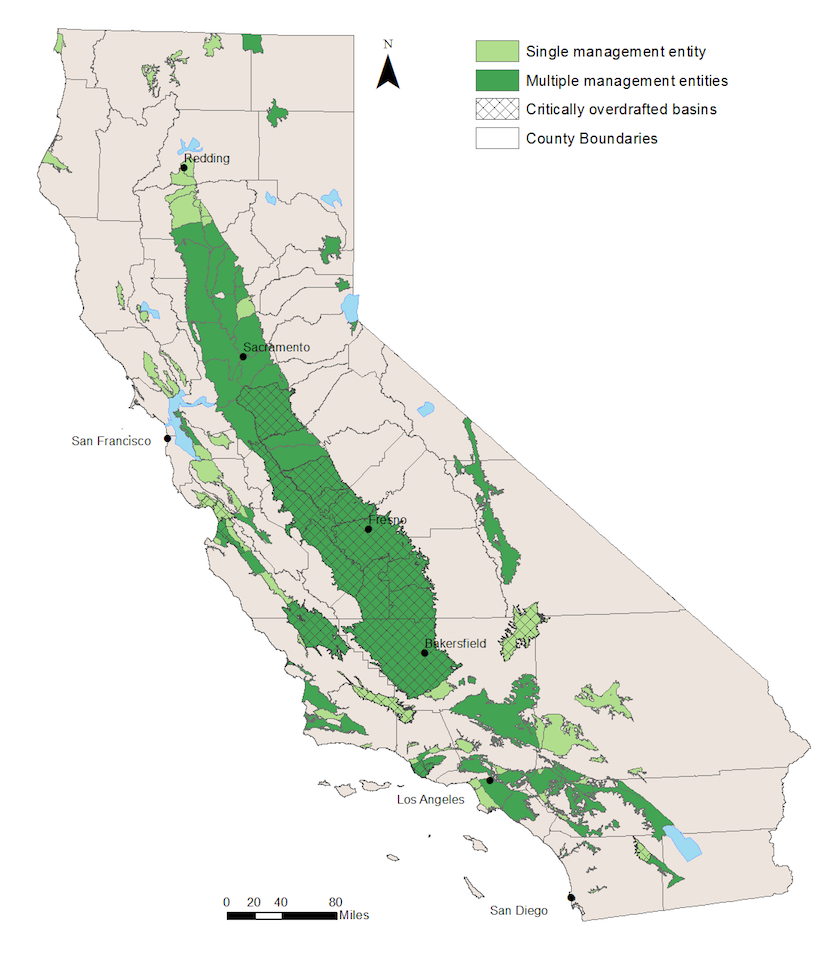

According to the study, about half of groundwater basins subject to SGMA have multiple GSAs, including many basins in the Central Valley, which has the majority of critically overdrafted basins. The paper focuses on case studies of three large agriculturally-oriented basins and describes their basinwide governance arrangements. Due to their large geographic scale and the presence of many individual groundwater pumpers, these basins face particular challenges in the GSP development process. Through discussions that extended over several years, stakeholders in these basins ultimately resolved these challenges by creating governance structures that operate at multiple scales, allowing some decision-making at the local level but coordinating GSP development at the basin scale. Building successful collaboration within a groundwater basin, the study finds, will require extensive time, dialogue and commitment on the part of all participants.

Coverage of high and medium priority basins by single or multiple management entities. These entities may take the form of 1) one or more GSAs; 2) an alternative plan; 3) an adjudication; 4) an "unmanaged" area; or 5) a combination thereof. Only high and medium priority basins are shown here.

This month, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) awarded $85.5 million in grants for groundwater sustainability projects that directly benefit disadvantaged communities as well as to support the GSP process undertaken by local agencies.

“Sustainable management of our groundwater basins is a critical element of making our communities more resilient in the face of climate change and drought,” said DWR Director Karla Nemeth in a press release on the new grants. “These funds direct critically needed resources to disadvantaged communities and newly formed groundwater sustainability agencies so that they may address regional water supply challenges now and in the future.”

The funds are a welcome sight for GSAs as they begin to kick the GSP development process into high gear, particularly in critically overdrafted basins.

“This funding will hopefully enable more participation and commitment on the part of nongovernmental entities as well as local agencies as they develop these plans. The people at the table are just as critical as the water you have available when it comes to creating a sustainable groundwater management plan into the future,” said Conrad.

Last week, DWR released the final Water Available for Replenishment (WAFR) report which shows the agency’s best estimate of how much water will be available to replenish groundwater resources in the state to help GSAs develop their plans going forward. The report shows that many regions will have to cope with limited water availability for aquifer recharge and recommends a diversified approach to managing water resources.

“The WAFR report makes it abundantly clear that a diversified water resources portfolio is needed at the local, regional and state levels,” said Nemeth. “If California is to simultaneously bring sustainability to its groundwater basins, cope with climate change, and meet future demands, water managers must embrace a comprehensive, innovative approach.”

This call for diversity in approach echoes the study’s findings that multiple agencies, perspectives and approaches are needed to solve the issues at play in groundwater basins that are hydrologically and socio-economically complex.

“If GSAs are going to succeed in meeting the requirements of SGMA and sustainably manage groundwater resources for the future, it’s going to take a lot of collaboration, discussion, and participation,” said Conrad. “The stakes couldn’t be higher.”

For more information, refer to the research brief on this work.

Meeting of the Yolo SGMA Implementation Working Group in April 2017.

![[Woods Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-woods.png)

![[Bill Lane Center Logo]](/sites/default/files/logos/footer-logo-billlane.png)