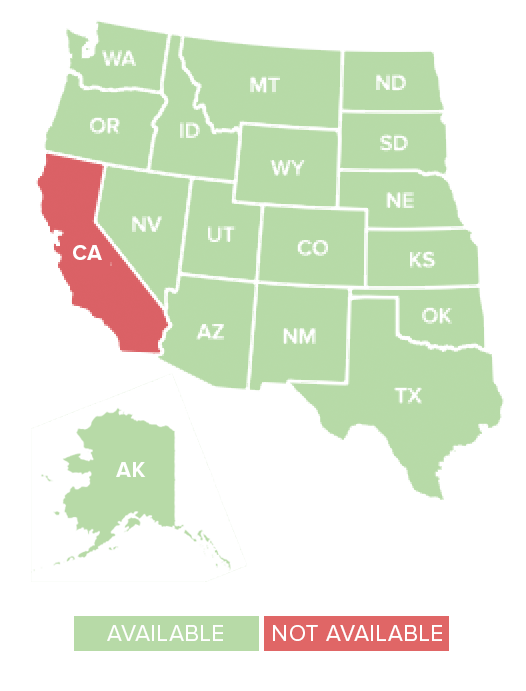

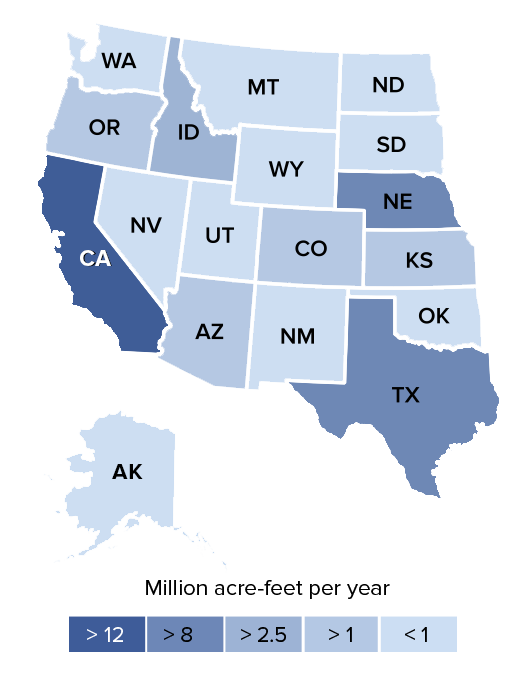

When it comes to groundwater data collection, California lags far behind other western states, most of which have much stricter disclosure requirements for water users. All this despite the fact that California pumps more groundwater annually than any other state in the US.

California’s groundwater resources are significantly depleted in many areas. With the ongoing drought and less surface water available, groundwater resources are under pressure as never before to meet drinking water and irrigation demands. To provide for present and future water needs, careful management of groundwater is essential.

Groundwater data are the critical foundation for water managers to both prevent problems and formulate solutions. In California, where groundwater makes up between 30-60% of the state’s water supply system, everyone benefits from good groundwater management, whether through direct use, or indirectly from the social, economic and environmental contributions associated with groundwater use.

A new study by Water in the West indicates that basic data is lacking in many of California's groundwater basins. As millions of acre-feet are pumped statewide each year, many heavily used basins have no record of

Nor are adequate data available on groundwater quality or aquifer characteristics.

Signed into law in September 2014, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act requires groundwater basins managed under Groundwater Sustainability Plans to monitor groundwater levels, groundwater quality, subsidence, and changes in groundwater-related surface water flows and quality. It also requires consistent data collection and sharing between water agencies managing each groundwater basin.

When it comes to groundwater data, California has little groundwater data compared to other western states, most of which have much stricter information disclosure requirements for water users. For example, a key metric needed for good groundwater management – well log data – is publicly available in every western state except California. All this despite the fact that California pumps more groundwater annually than any other state — nearly one-fifth of all the groundwater pumped in the U.S. annually.

Given the importance of consistent and reliable groundwater data for good management, it is unsurprising that many western states have legislated requirements for agencies to collect it and make it available to the public.

California’s lack of data collection is not the result of ignorance about its importance, but the victim of chronic underfunding and politics. In 2009, California legislators passed a bill (SBX7-6) creating the California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring (CASGEM) program to track seasonal and long-term trends in groundwater elevations in the state’s groundwater basins over time. The law also requires collaboration between local monitoring entities and the Department of Water Resources to collect and disseminate groundwater elevation data in a public database. Despite its potential, CASGEM has not been well used and has had limited success due to the lack of dedicated program funding.

Furthermore, while the drought and related cutbacks on surface water supplies are motivating groundwater users to drill new or deeper wells in increasing numbers, California law actually prohibits public access to well logs compiled by drilling companies, even though drillers are required by law to submit the logs to the California Department of Water Resources. Previous efforts to change this have fallen short. California is the only western state to restrict access to well logs.

While California still lacks a comprehensive groundwater management regime, the obstacles may be shifting because:

In a dramatic shift, the Association of California Water Agencies (ACWA) has recently come out in favor of broader groundwater data collection and sharing, including levying fees on groundwater pumping (which requires metering to know how much water is extracted).

If California begins moving toward more comprehensive data collection and sharing, what are the pieces of information that are vital to effective management?

A study by Water in the West has determined that the collection and sharing of five metrics are key – at a minimum – to effective management of groundwater resources. Each is important on its own, but they are all intertwined.

Information on location, depth and subsurface geology, collected at the time a well is dug or deepened

Well logs have been required in California since 1949, but they are provided to DWR in hard copy, making data access and analysis difficult. Additionally, California law prohibits nearly everyone, besides government agencies, from accessing the data without the owner’s consent. The lack of access to well log data negatively affects groundwater management in California, as these data are critical to understanding the size and geographic distribution of aquifers — or water-bearing formations — within a groundwater basin. Well logs can provide insight into where water best infiltrates into groundwater aquifers. With this data, managers can better manage groundwater through an improved understanding of the aquifer system – by protecting groundwater recharge areas from development, or enhancing recharge by targeting their managed aquifer recharge projects to these areas. In addition, the well construction information from well logs is essential in understanding the depths from which groundwater is produced in an aquifer.

Groundwater elevation data, collected over the long term and analyzed for trends, can alert managers to the potential for a variety of problems. How many local wells will dry up if groundwater elevation declines? What rivers and ecosystems depend on groundwater to maintain instream flows, and how will increasing pumping or decreasing quality affect them? At their simplest, groundwater elevation data can warn of aquifer depletion and point to changing energy costs. Combining groundwater elevation data with groundwater quality and geologic information signals to water managers the potential for saltwater intrusion, land subsidence, and the spread of contaminants — critical to protecting public water supplies and infrastructure from potentially irreversible harm. Understanding groundwater elevation trends can also help determine how much water needs to be recharged into the basin. Different well locations throughout the basin can provide information on where management efforts are needed. The more wells there are, the finer the resolution.

Because groundwater pumping is the largest form of withdrawal from aquifers, production metering is critical to answering many questions about the health of a groundwater basin, such as: How does pumping cause changes in groundwater elevations? Are we using more water than is currently being recharged? How can we design effective measures to influence pumping or increase recharge?

Knowing the amount of water being pumped and recharged into an aquifer can give water managers the information they need to make decisions and take action to sustainably manage groundwater through seasonal changes and through wet years and drought. Production metering data also can help in the development and administration of flexible tools that help groundwater users deal with scarcity, like water marketing and incentive programs, to increase water use efficiency. Finally, in a court context, a record of water usage over time is necessary for groundwater users to prove their legal rights.

Understanding groundwater quality and how it is changing over time is important to protect public health, as well as the long-term health of aquifers. In addition to the natural variability in groundwater quality that can exist across and within an aquifer system, a variety of man-made pollutants including fertilizers, pesticides, and petrochemicals can infiltrate into the ground and contaminate aquifers. It is vital to take all steps necessary to prevent contamination and to address it early if it happens. Understanding water quality also can help in protecting agricultural lands. For instance, using groundwater high in salts can damage crops and soils. Saltwater intrusion into freshwater aquifers along the coast can become a problem as groundwater pumping increases. As groundwater elevations decline, both man-made and naturally occurring contaminants in an aquifer can become concentrated, requiring more costly treatment or well abandonment.

Groundwater modeling helps water managers understand what’s happening in the aquifer and make predictions about trends and changes given different scenarios (pumping, climate, land use, etc.). Water managers, in turn, can use these scenarios to communicate with land use planners, policy makers, other agencies, and the public to make more informed decisions around groundwater, addressing questions such as: How does pumping groundwater at different locations influence groundwater elevations and quality? How will land use changes in this region affect groundwater recharge to the basin? Can we supply current groundwater users without adverse impacts? Can we supply additional groundwater users without adverse impacts? What happens if we continue pumping the way we have been?

To get an understanding of whether basic groundwater data is collected and shared for different basins in California, Stanford graduate student Justin Maynard collected and analyzed publicly available information – management plans, reports, regulations, and judgments (in the case of adjudicated basins) – for approximately 150 basins in California. These include the the 130 or so high and medium priority basins and subbasins identified by the Department of Water Resources’ basin prioritization process. A simple scoring system was applied to each basin, with points given for how well they collected and shared key groundwater data - well logs, groundwater elevations, production metering, and groundwater models (the Missing Metrics described above). Scores from each basin were collected and analyzed based on California’s 10 hydrologic regions.

| Hydrological Region | Collect 1 |

Share 1 |

Digital 1 |

Collect 1 |

Share 1 |

Digital 1 |

Collect 1 |

Share 1 |

Digital 1 |

Develop 1 |

Overall Max: 10 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Lahontan | 89% | 0% | 0% | 89% | 89% | 0% | 89% | 83% | 78% | 89% | 6.0 | ||||

| Colorado River | 83% | 0% | 0% | 83% | 83% | 0% | 100% | 58% | 0% | 50% | 4.6 | ||||

| South Coast | 84% | 0% | 0% | 62% | 57% | 1% | 84% | 54% | 34% | 50% | 4.3 | ||||

| San Francisco Bay | 71% | 0% | 0% | 29% | 29% | 0% | 71% | 64% | 29% | 71% | 3.6 | ||||

| Tulare Lake | 88% | 0% | 0% | 13% | 25% | 0% | 88% | 56% | 31% | 50% | 3.5 | ||||

| Sacramento River | 97% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 3% | 0% | 94% | 70% | 39% | 24% | 3.3 | ||||

| Central Coast | 74% | 0% | 0% | 15% | 22% | 0% | 74% | 54% | 20% | 33% | 2.9 | ||||

| North Lahontan | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 57% | 0% | 14% | 2.7 | ||||

| San Joaquin River | 78% | 0% | 0% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 78% | 17% | 22% | 33% | 2.4 | ||||

| North Coast | 33% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 11% | 0% | 33% | 28% | 17% | 33% | 1.6 |

Our research found that groundwater basins are most commonly managed using at least one of the following four approaches: management plans, ordinances, special act districts, or adjudication. The majority of groundwater management in California is done using management plans, which allow only for the collection of groundwater elevations, quality, and production data only from public supply wells, at their discretion. Data is not included from private wells, which in many areas of the state constitute the largest withdrawals. According to our research, basins with groundwater models tend to be those with one of these four active management types.

Many basins collect data, particularly on well logs, groundwater elevations and water quality. However, the sharing of these data is much less common, due in part to antiquated laws that prohibit sharing information and the common use of file formats that do not allow for easy data sharing and use in analysis (such as PDFs). South Lahontan is the only hydrologic region in California that makes its data more readily available in digital form. Production metering data collection and sharing is generally very low across all hydrologic regions. The South Lahontan, Colorado River, and South Coast regions do a better job of collecting and sharing production data than other regions, but even they do not make these data available in a publicly accessible digital format.

Total scores on groundwater data collection and sharing across the state as a whole were low, with 9 of the 10 hydrologic regions scoring less than 5 out of a possible 10 points. The South Lahontan hydrologic region scored the highest, with 6 points.

Despite the fact that as a state California lags behind, there are quite a few groundwater basins that maintain detailed data collection and sharing of some key metrics, illustrating that there is nothing inherent about California’s legal and institutional framework that prevents good data programs. Examples of innovative approaches to groundwater management in California, including data collection and sharing, are highlighted here.

Collecting technically adequate groundwater data is not enough. The inherently public nature of groundwater management requires groundwater managers to disseminate information that will garner public support for effective groundwater policies and management.

In contrast to data – which are often numbers given without context – information communicates the actual and potential severity of the larger consequences of groundwater conditions and management decisions in light of local circumstances and future management plans. Where possible, information should answer questions that are important for the public to understand, such as: Is the groundwater safe to drink? Is my well going to continue to supply me with the water I need? How many local wells will dry up if groundwater elevations continue to decline?

Information is only good when it is put to use. It has to be tied to an implementation plan and an ability and willingness to regulate where necessary. There need to be consistent yet flexible standards for data and information across local districts, regions, and the state in order to be transferable and comparable. There must also be sufficient investment in monitoring and dissemination.

California currently encourages collection of data but does not require it. The state also provides little in the way of uniformity and clarity around data collection, methodology, evaluation, and reporting. Adequate groundwater data and modeling are critical to enable and empower groundwater managers to prevent problems and formulate solutions. Just as it would be impossible to manage one’s finances without a clear understanding of the sources and amounts of revenues and expenses, managing groundwater without the five basic metrics (at a minimum) just doesn’t add up in the long term.

While some may see greater data collection, monitoring and reporting as a threat to local control of resources, the contrary is actually true. Better information improves the ability of local agencies to sustainably manage their own groundwater basin, making it is less likely that the state will need to be involved under the auspices of an emergency.