Now in its third year, the current drought reminds us that California’s water supplies are limited. Calls are growing louder to enlarge dams – or build new ones – to expand the state’s water storage capacity. But far less attention is given to a cheaper but less visible option – storing water under our feet.

Groundwater storage represents both a practical solution to the state’s additional water storage needs and a tool to help manage groundwater more sustainably. Groundwater levels are continuing to decline across the state, not just from California’s current drought, but from decades of chronic overuse. Augmenting water supply through recharge into aquifers presents a cost-effective way of increasing the availability of groundwater for the inevitable dry times ahead.

New research by Water in the West shows that groundwater recharge is a cheaper alternative to surface storage. In fact, researchers found that the cost of recharge is cheaper than many other water supply options at $90 to 1,100 per acre-foot, or at a median cost of $390 per acre-foot, which broadly agrees with published values.

See below for more details on how recharge compares, cost-wise, to other storage methods.

In addition to being cost effective, recharge offers a number of advantages compared to surface water storage methods:

Groundwater recharge can act as a barrier to seawater intrusion in coastal basins and to the migration of contaminants. Other potential benefits include improving flows in rivers and streams, flood control, and wildlife and bird habitat.

To users frustrated by the volatility and uncertainty of surface water imports, groundwater recharge and storage also allow for more local control over water resources.

No one knows the exact amount of water that can be stored within California’s 515 groundwater basins. California’s Department of Water Resources estimates the total storage capacity at somewhere between 850 million and 1.3 billion acre-feet. In comparison, surface storage from all the major reservoirs in California is less than 50 million acre-feet.

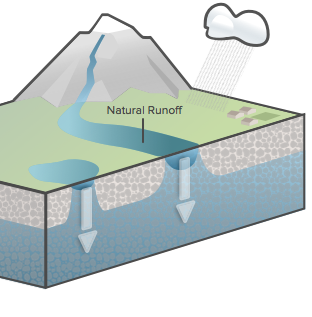

In order to replenish aquifers, water must get into the ground – a process called recharge. Recharge can happen naturally or artificially.

Natural recharge is simply rain and streamflow that soaks into the ground to an underlying aquifer. Unfortunately, urban development often creates hard surfaces such as roads, rooftops, and parking lots that prevent rain from soaking back into the ground. While there is an increasing focus on identifying and protecting groundwater recharge zones (areas where the recharge to underlying basin is highest) these measures are often not enough to prevent chronic groundwater depletion.

Natural recharge is simply rain, snowmelt and streamflow that soaks into the ground and an underlying aquifer.

Given that natural recharge can’t keep up with our demands for groundwater, humans can help to recharge the aquifer “artificially” by purposefully moving water into the underlying groundwater basin for storage.

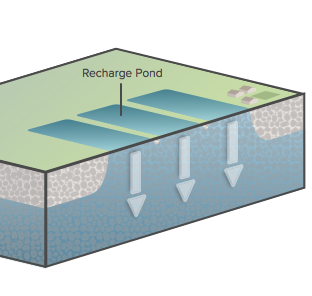

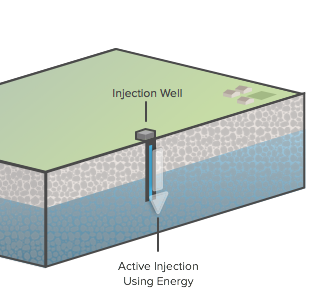

The most common methods for direct artificial recharge are using recharge ponds and injection wells.

The most common method used, recharge ponds are constructed surface basins that allow water to slowly infiltrate through the soil into the underground aquifer.

A more energy-intensive method that uses high pressure pumps to actively ‘push’ water into aquifers.

Of course, the key ingredient in any recharge project is water. Typically, it has been surface water taken from rivers and streams during high spring flows – times when demand is lower.

But increasingly, alternative sources of water are being used for recharge as water becomes more scarce. What were formerly seen as liabilities – treated wastewater, stormwater, and agricultural runoff – are now all starting to be used for recharge. Perhaps as a sign of what is to come, jurisdictions in the Monterey Bay and Salinas Valley are fighting over rights to use agricultural runoff.

Recycled water of the highest quality is also being put back into aquifers for storage in many places such as Santa Clara County and Orange County.

Besides water, other key conditions needed to make an artificial recharge and storage project work are:

In addition to having the right conditions for recharge, other critical elements must be in place: funding, permitting, and oversight by a water agency or entity to manage the operations and allocations.

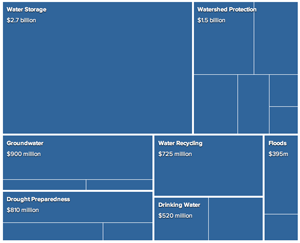

On November 4, 2014, Californians approved the $7.5 billion water bond, the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014. You can read more about the funding categories in our infographic. Specific agencies will determine how funds within the water bond will be allocated.

Although relatively cheap, the costs of groundwater recharge and storage can still outstrip the finances of local communities. State assistance has therefore been critical in supporting local entities for water management, including recharge projects.

Research by Water in the West shows that state grants have provided an estimated $1.15 billion (2014 dollar value) in total funding for groundwater recharge and storage projects. Financing for these projects has come from several voter-approved bonds: Propositions 84, 1E, 50 and 13. Proposition 13 was solely dedicated to groundwater recharge and storage; the others were for general water management programs that integrated groundwater recharge and storage into projects.

The funds that supported recharge created a first wave of projects that are helping to alleviate California’s groundwater problems. However, with most of those bond programs at or near the end of their lifespan, it is a good time to evaluate the results of these initiatives and draw lessons for the future of groundwater recharge.

In order to gain a better understanding of recharge projects in California and their role in groundwater management, Water in the West researchers obtained all available grant applications submitted to the Department of Water Resources for the four recharge-related grant programs listed above. This new study evaluated 136 grant applications filed over the past 14 years that were wholly or partly devoted to recharge. Funding requests ranged from feasibility studies and planning to construction.

While these grant applications do not reflect all of the groundwater recharge projects in California, they offer a good overall proxy for the demand, scope, nature and possible impact of these projects on California's groundwater problems.

Based on the grant applications obtained by Water in the West, the anticipated annual recharge capacity of funded projects is 306,727 acre-feet per year. However, if we consider both the awarded and declined recharge applications studied, the recharge potential is closer to 785,000 acre-feet per year.

Both the higher and lower numbers are likely to be underestimates since only 30% of the Proposition 13 applications considered by DWR were available for analysis (57 out of 190).

Out of 136 recharge-related grant applications reviewed by Water in the West, 78 were awarded.

The 78 awarded projects we studied were awarded at different funding levels. This map shows all grant proposals sized by their requested budget and shaded by granted percentages, including unfunded applications (0%). The number of unfunded and partially funded applications is evidence of unfulfilled need for recharge across the state.

Funded projects were concentrated in the Central Valley and in southern California – areas with groundwater basins that have been identified by the Department of Water Resources as higher priority and having a greater need.

The overlap of recharge projects with overdrafted groundwater basins suggests that there is capacity for recharge in many areas and there is interest in using recharge as a tool to address local needs and concerns.

There was considerable diversity in the purpose of the recharge-related projects submitted for grant funding. Some recharge projects would help replenish local groundwater supplies during wet years, so that it can be utilized during dry periods (i.e. conjunctive use and/or groundwater banking) while others would help mitigate land subsidence.

Some projects requested funding to buy and regrade land for recharge ponds. Others wanted to establish a groundwater bank. Some projects appeared to frame recharge as an ancillary benefit to maintenance work like dredging silt from reservoirs.

Water in the West's new research findings highlight the potential for groundwater recharge and storage to improve water reliability and security in California. However, several factors must be addressed at the local, regional, and state levels in order to take advantage of the opportunities that groundwater recharge presents.

Groundwater management is needed to ensure sustainability of groundwater resources. A number of groundwater districts have been doing this successfully for decades. Without some ability to manage groundwater demand, some agencies may be reluctant to implement recharge programs.

Funding is necessary to supplement local resources for recharge projects in many places and to aid in the implementation of groundwater management goals. Besides bonds, options for water funding include increasing the state sales tax, levying a statewide surcharge on water utility bills, providing groundwater management agencies the authority to levy fees on pumpers or other water users, or a combination of these options.

Slide the bars below to see funding available according to each hypothetical option.

Source: Estimates for water and sales tax surcharge revenues by Public Policy Institute of California

Data needs and sharing are crucial for improved groundwater management. Information on groundwater levels, along with increased transparency and accessibility of existing data, are necessary to to prioritize recharge needs and locations.

Regulatory certainty is key to investing in groundwater recharge and storage in order to guarantee that users who put water into the aquifer will be able to retrieve their investment in the future.

Research into potential issues around groundwater recharge is needed, both statewide and for individual basins, to ensure the successful implementation of recharge projects. Questions of groundwater contamination, impacts of surface flood flow diversions on groundwater-dependent ecosystems, and chemical interactions between recharge water and aquifer water are a few issues that need to be identified and studied moving forward.

Researchers found that California’s future water supply will best be met through a combination of approaches, including groundwater recharge, improved groundwater management, water conservation, and water recycling, not through the large surface water infrastructure projects that typified the last century.

Groundwater recharge will undoubtedly play an important role as part of a diversified water supply portfolio for California. It is proven, cost effective and presents a significant opportunity to help prepare the state for drier times that are sure to come. But how quickly?